Navigation

Tactics

The bombing of civilian targets, including transport centers or industrial facilities by large bi-planes or even Zeppelins was utilized by both sides in the First World War. At the outbreak of the Second World War many thought aerial bombing was to be the great weapon of victory. However the first bomber raids in 1939-1940 were inconsistent and unorganized. In daylight squadrons would take off, fly to the target and drop their bombs on what they saw. The German fighters quickly demonstrated that daylight attacks were costly and Bomber Command switched the raids to night. The next tactical change took place as the Nazis developed a bigger night-fighter force, which could find the attacking bombers using ground and radar equipment. As the attackers were often spread out, they became easy targets, as a one-on-one battle was often won by the fighter. This led to the "Bomber Stream". This was a tight grouping of bombers that attacked in force. It was a well-controlled convoy that followed a designated route to and from the target.

There were no Allied fighters to accompany the bomber stream, as none at the time had the range. The bombers had to protect themselves from the German fighters.

The next development was the special Pathfinder squadrons, whose tasks were to mark the significant points on the route and over the target areas. The Pathfinders used a variety of flares and coloured markers.

On the eve of Nuremberg "Bomber Streams"of up to 1,000 aircraft were attacking at night, without much fighter support, following a set route to and from the objective. The objective was marked by the Pathfinders.

Electronic Aids and Radar

The whole Air War came down to a game of "cat and mouse". The Allies tried to hide the bomber stream, while the Germans tried to find it. To disguise their intentions much use was made of radio signals and radar, by both sides. Each side would come up with new methods to fool the enemy while the enemy would find ways to jam the others Signals.

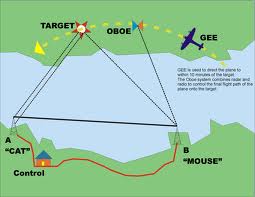

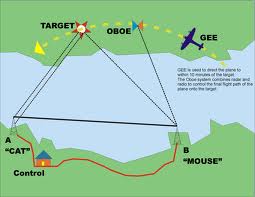

Throughout the ebb and flow of development and deployment of electronic methods to facilitate navigation, identification of hostile aircraft, and defense, Bomber Command resorted to a variety of tactical and technical innovations in its campaign against Nazi Germany. Amongst the first navigation aides were Gee and Oboe. Gee was the earliest navigational aid and the Germans quickly learned how to jam the signals and therefore its use was limited to the early operations of Bomber Command.

Oboe was based on signals sent from separate transmitters in England and where the two signals intersected was the target. Pathfinder aircraft were equipped to pick up the beams, and therefore bomb accurately. However due to the curvature of the earth, the further away from England you were the higher the altitude required to pick up the waves. Consequently Oboe was not employed against distant targets such as Nuremberg.

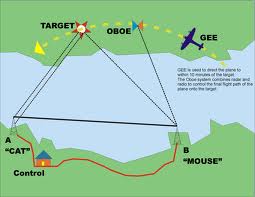

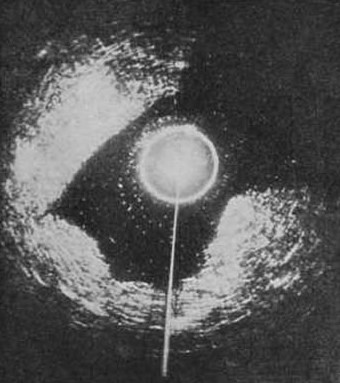

Bomber Command's principal electronic navigation aid was H2S or as it was known, "Stinker". H2S was a radar set in the bomber. It had a small screen on which the terrain below was reflected. With the right operator it could give important information about the whereabouts of the aircraft.

The bomber's tactic was to use Gee on the outward-bound legs to confirm positions and determine wind velocities until German jamming masked the transmissions. That generally occurred soon after the bomber stream reached the continent. Consequently the bomber crews used H2S to help pinpoint their positions in order to determine wind velocities at the higher levels. Accurately determining the winds was a critical part of a raid. Should the winds spread out the bomber stream, they would be easy targets for the German night-fighters. To accurately gauge the winds, the H2S findings, together with results transmitted every half-hour from lead bombers, known as the Zephyr system, were intended to keep the bomber stream together.

The object of all the navigational aids was to get the maximum number of aircraft to and through the target in minimum time, and to minimize the possibilities of airborne interceptions. The problem was that the German Luftwaffe, could pick up on the H2S signals and find the bomber stream that way. The great number of Bomber Command aircraft involved in a raid made tracking the stream relatively easy for German ground radar installations. The wholesale use of H2S by the RAF crews during operations maximized the possibilities of interception by night fighters.

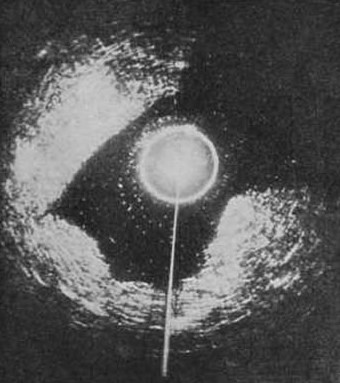

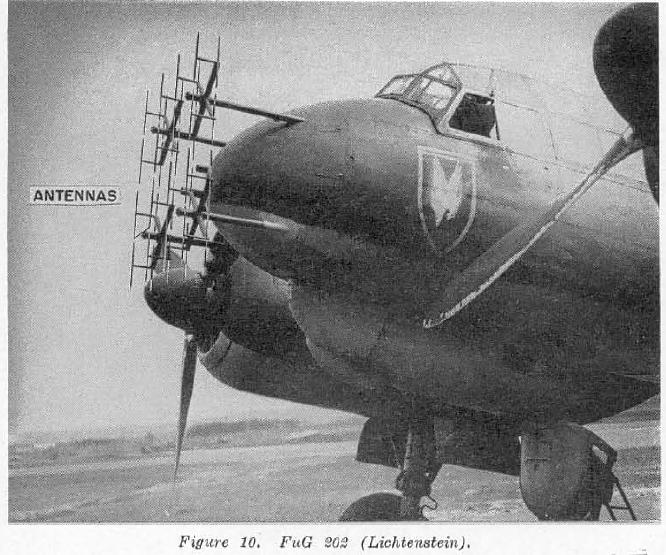

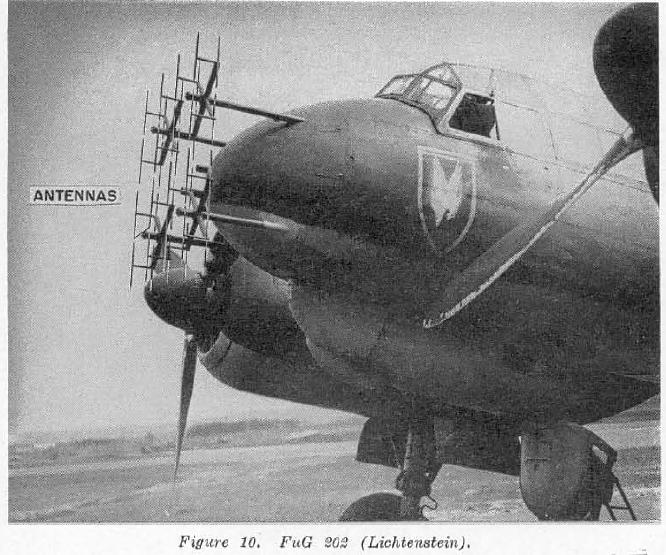

The Germans were no fools and they quickly developed airborne electronic aids to nullify the Allies' advances. They produced a number of their own counter-measures, such as Lichtenstein, SN - 2, or Naxos.

Window was a surprising successful development by the RAF, that for a brief period gave Bomber Command an advantage. Window was strips of aluminum that would be dropped by the millions by bombers that would wreak havoc with the Nazi communications. For a few months in 1943, particularly when bombing Hamburg, Window was the advantage. But once again the Germans developed a system, known as SN-2, that could see through Window. On the night of the Nuremberg Raid many German fighters were equipped with SN-2.

Another airborne jamming device, Airborne Cigar (ABC), was also used in conjunction with transmissions of false instructions broadcast by German speaking Royal Air Force crew members. These transmissions were intended to confuse enemy night-fighter crews by interfering with the steady stream of information the German pilots received in the air. Of course to do this the Allies had to know the frequency bands on which the Germans were communicating. Not surprisingly the Luftwaffe constantly varied frequencies.

Squadron RAF bombs over the target during a daylight raid.

The large aerials on top of the Lancaster's fuselage are the antennas for the Airborne Cigar system.

Serrate was a radar detector device designed to provide bearings on Luftwaffe fighter radar transmissions. Mosquitoes equipped with Serrate were deployed in the vicinity of known enemy beacons or airfields. The Mosquitos would then attack German fighters as they left the airfields or collected near the beacons.

However the presence of large numbers of bombers made differentiation between friend and foe extremely difficult. Consequently, and unfortunately for the Bomber Command force, ABC and the Serrate Mosquitoes achieved very little success on the night of March 30th/31st, 1944.

H2S

German

SN-2

ABC

Seratte

A Beaufighter fitted with Mark IV radar, the transmitting antenna may be seen on the nose of the aircraft, the receiving antenna are fitted to the wings

Other technical aids designed to increase the bombers' chances in their confrontations with enemy fighters that came on stream in 1943 and early 1944 were even less successful. Boozer was a passive device developed to pick up aerial transmissions from German fighters as well as those emitted by ground stations. It depended upon a system of lights that confirmed detection by the enemy. A yellow lamp signified the presence of enemy fighters; a red lamp confirmed detection by ground installations. As it turned out, enemy transmissions over its territory were so numerous that the lights remained on permanently, distracting and unsettling the bomber crews. Most switched off Boozer, relying instead upon vigilance, experience and luck for survival.

Monica was an active warning system installed at the rear of Halifax and Lancaster aircraft. It depended upon aural returns to indicate the presence of aircraft astern. Unfortunately Monica was unable to differentiate between friendly and hostile aircraft and the continuous clicking over the earphones proved to be an irritant rather than a help. The Monica responses were therefore ignored, or more usually, the device was switched off. A fourth technical device, Fishpond, was in effect a second H2S mounted horizontally at the rear of the aircraft. It showed aircraft in the bomber's immediate vicinity as spots or blips of light on the cathode ray screen. Those which maintained their position relative to that of the bomber were deemed to be other bombers. Any blips that converged upon the bomber were considered to be hostile interceptors. Like Boozer and Monica, difficulties of differentiation between friend and foe made Fishpond less than effective as a defensive aid.

Monica

Evasive Tactics

In addition to the radar assistance, survival depended on the crew's senses, operational experience, and the corkscrew manoeuvre. The corkscrew, although a fairly effective tactic under normal circumstances, was less effective because the heavy loads carried by Halifaxes and Lancasters considerably inhibited their maneuverability. On receiving a gunner's warning of an impending attack the corkscrew required the pilot to turn sharply and simultaneously dive towards the approaching fighter, then quickly reverse direction while pulling up his aircraft into a steep climb. It was a violent manoeuvre that often scattered the navigator's dividers, pencils and protractors, and sometimes brought crew members other than the pilot to the point of nausea. Nevertheless, sound judgement and accurate directions from the gunners, together with quick reactions by the pilot, were the "sine qua non" of the corkscrew. Repeating the manoeuvre for as long as necessary in order to evade the attacker, while giving the gunners opportunities to shoot it down was however, physically demanding. In daylight the corkscrew was largely ineffective against nimbler single-engine fighters; but under cover of darkness it enabled the bomber to contend with a fair degree of success. Some crews resorted to the corkscrew throughout their time over enemy territory; others only when attacked. One crew from 514 Squadron reported corkscrewing for an hour during the Nuremberg raid in order to hold off fighter attacks. A Luftwaffe pilot reported the same night that he failed to complete an attack against a Lancaster because it successfully resorted to the defensive manoeuver for 45 minutes!

"Spoof's"

Another tactic meant to fool the German night-fighters was the "spoof' or diversionary attack. When a raid was mounted a certain number of aircraft would be used on spoofs. Each spoof would be intended to divert the German fighters away from the Bomber Stream.

The Route

The route the Bomber Stream would take was also predetermined and designed to try and fool the Germans. It was rarely straight and usually included several dog's legs. The route to the target was usually the most dangerous as the bombers were fully loaded and slow. The courses attempted to avoid German anti-aircraft (Flak) positions along the coast, or near major centres. To be avoided at all costs were the Luftwaffe's fighter beacons, the collection point for that region's night fighter forces.

The German Defences

By the spring of 1944 the German defences protecting their industrial heartland were quite efficient. Along the coast and around the cities the Germans had a sophisticated system of anti-aircraft guns and searchlights. In fact they had an estimated 20,625 flak guns and 6,680 searchlights deployed. Germany had taken a pounding but they were fighting back. The strength of the defences was its communications, intelligence and electronic monitoring of signals, and how that information got into the hands of their pilots.

As in the British experience, German radar played a significant role against the Allied bomber offensive. Foremost in the system were the early warning Freya units which were capable of detecting aircraft movements in Britain. This system could pick up the H2S waves as soon as the bombers in started up. This information was then passed to the fighter control rooms and the game of finding the Bomber Stream would start. The level of activity could tell whether what they found was the real thing or a "spoof'. The German fighters would take to the air, constantly being in touch with the control room. In fact it was this system the ABC Cigar was intended to disrupt. The night-fighters would collect near the beacon closest to the anticipated path of the bombers. Then the fight would begin.

Numerous static and mobile Wurzburg variants provided airborne fighters with information to intercept the Stream. It also controlled flak installations as well as directing the blue beam master searchlights dreaded by all Allied aircrew. The combination constituted a formidable defensive organization ranged across occupied Europe and the German heartland. By the time of the Nuremberg raid German scientists too had developed efficient airborne interception radar units, Lichtenstein, Flensberg, the SN-2 and Naxos, which enabled Luftwaffe night fighters to detect H2S emissions from Bomber Command aircraft up to a range of 50 km. This also assisted the enemy in closing in for deadly interceptions.

German Fighter Tactics

Tame Boar

By the spring of 1944 the Reich Air Defence developed what became known as the Zhame Sau or Tame Boar system, which emphasized pursuit within the bomber stream. During a typical Tame Boar sortie the night fighters, usually the Messerschmitt 110 or the Junkers 88, would take-off and fly to a given radio beacon, using a homing device for navigation. Once in position they flew a holding pattern until the ground controller identified the position of the bomber stream. Then the fighters were infiltrated into the bomber stream (often 100 km long) where interference from electronic counter-measures such as Window was less pronounced and detection by the bombers difficult. Once close they used their short-range radar to locate and close in upon their prey. ABC Cigar was often used to try and decoy or confuse the Tame Boar pilots.

Wild Boar

In addition to facing the Luftwaffe's Tame Boar night-fighters swimming in the Bomber Stream, Bomber Command aircraft also had to contend with attacks from faster, more manoeverable single-engined fighters. These fighters were not equipped for night fighting, but could be utilized under specific circumstances. For the most part the Messerschmidt Bf 109's and Focke-Wulf 190's operated over or near targets in order to take advantage of the illumination afforded by flares, searchlights and fires started by the incendiaries and high explosives dropped by the attackers. Together with reflections from cloud cover, the searchlights and ground fires silhouetted the bombers enabling the nimbler fighters to swoop in from above in traditional attack fashion. They had to be very careful not to be hit by their own anti-aircraft guns, so they usually operated at altitudes of 30,000 feet or more, well above the bombers.

Code named Wilde Sau (Wild Boar), the single-engined attackers, entered the battle when the target had been determined. Piloted by less experienced, comparatively undisciplined pilots the Wild Boar squadrons achieved relatively minor returns in relation to their losses. They were often brought down by their flak, accidents, and fuel shortages.

Over Nuremberg the weather conditions mitigated against any significant intervention on their part.

Schräge musik

By the time of the Nuremberg attack a substantial number of the Luftwaffe's twin-engined night fighters were equipped with two upward firing 20 mm cannon. Known by the code name Schräge Musik, the arrangement consisted of the weapons mounted in the cockpit enclosure behind the pilot, at an angle (usually sixty degrees) to fire upward and forward. Upon sighting and visually identifying his quarry silhouetted against the night sky the fighter pilot positioned himself slightly behind and a hundred to three hundred feet below the enemy aircraft. Since the Ju88s and Mell0s were only slightly faster than the four-engined bomber it was comparatively easy to sidle into and maintain firing position for the brief time necessary to ensure a kill. Using a periscope gun-sight the more skilled fighter pilots aimed at a point between the Halifaxes' or Lancasters' wing roots, or between the two engines. A short burst was usually enough to set them on fire, and in some cases to give a few of the seven-man bomber crews time to bail out. Since downward visibility from the Halifax and Lancaster rear turrets was almost negligible most bomber crews never realized where the attack originated and could not specify how they had been shot down.

Mother Nature's Defences

Bombing was dependent on a number of variables associated with Mother Nature, such as the season, the weather, the winds, the clouds and the moon. Because the bombing took place at night it was necessary to have the correct hour of darkness. Therefore targets deep inside Germany could only be bombed on long winter nights.S evere weather could ground a mission. So could too much cloud or too little or the wrong type of clouds. No cloud would give enough cover for the bombers to conceal themselves from the fighters. Low cloud would obscure a target, sometimes causing an operation to be called off. Consequently the weather forecast was crucial to the success or failure of a raid.

The phases of the moon were also important as the high moon was considered too bright, and would give the night-fighters an advantage. All these items would have to be taken into consideration as to whether a raid was a "go" or was "scrubbed".

Gee Navigation

Gee was a hyperbolic navigation system.

GEE transmitters sent out precisely timed pulses. The system comprised three Gee stations, one master and two slaves. The master sent a pulse followed two milliseconds later by a double pulse. The first slave station sent a single pulse one millisecond after the master's single pulse, and the second slave sent a single pulse one millisecond after the master's double pulse. The whole sequence repeated on a four-millisecond cycle. On board the aircraft, the signals from the three stations were received. The on-board equipment would display the two slaves' signals as blips on an oscilloscope type display.

Since the display timing was controlled by the pulses from the master station, the display equipment gave the difference in reception time of the pulses and hence the relative distance from the master and each slave. The aircraft carried a navigation chart with several hyperbolae plotted on it. Each hyperbolic line represented a line of constant time difference for the master and one slave station. All the navigator had to do was find the intersection of the two hyperbolae representing the two slave stations.

William Uyen

November 18, 1943 HisStory during the Air-battle of Berlin March 31, 1944